why I do this work

Never in a million years could you have told me that one day, I would become a “voice teacher.”

As a kid, I was so anxious on the way to voice lessons that I’d break out in hives. By the time I reached adulthood, I could barely stand up straight in an audition without bracing or holding my breath. I loved to sing—but the binary structure of music training made me feel rigid, stifled. I was either “good” or “bad,” “sharp” or “flat,” doing it “right” or “wrong.” One cracked note could send me into a full spiral. (How I went on to have any career as an actor is beyond me.)

Over time, singing stopped bringing me joy. I’d still show up at karaoke or do a summer stock musical, but something had shifted. On a deep level, as I lost my connection to music, I lost the identity of being a “singer.” Even as I booked roles as an actor, I felt out of control in my voice and body—especially in auditions or rehearsals. It often felt like my nervous system was calling the shots.

The anxiety never left. It clung to me like a shadow, and I assumed there was something inherently wrong with me. I hadn’t yet learned that what I was experiencing wasn’t just “nerves”—it was something deeper. And if you’re a human being on planet Earth, you’ve probably experienced it too: trauma.

The body remembers what the mind cannot.

When we experience trauma—especially the subtle, chronic, or developmental kind—the nervous system stores a sensory snapshot of the threat. Later, when we’re vulnerable or exposed (onstage, in a meeting, in a conversation that matters), that alarm can go off again. Suddenly, you’re flushed, blank, tight in your chest. You lose your train of thought. Your voice shakes. You disconnect.

Once the alarm is sounded, the brain sends notifications to the rest of our body via the nervous system to prepare for the perceived danger for protection. We feel a surge of energy by way of sensation— our skin tingles, legs shake, palms get sweaty, chest can feel tight (just to name a few). Sound familiar? This is called a "trauma response,” and this is how anxiety can, quite literally, steal the show. Pretty difficult to effectively speak or sing when this happens. In fact, pretty difficult to function at all.

It doesn’t just happen to performers. I work with lawyers who can’t speak up in court, professors who feel physically ill before giving lectures, therapists who shut down when their client gets angry, and creatives who go mute at the mic. What they all have in common is this: the voice goes where the body goes. If your nervous system doesn’t feel safe, your voice won’t feel free.

When we are triggered, we can’t access our creativity, imagination, or our communication skills— all things vital to becoming a collaborative, healthy, and inspired artist.

All along, there was nothing "wrong" with me. I had experienced childhood trauma that simply wired my nervous system for survival without having the resources to get me out of it. What I needed was a trauma-informed voice coach who could help me understand how it had been limiting my artistic potential and then-- most importantly--what to do about it.

That's why I do this work.

And if you’re still reading, maybe a part of you is ready to reclaim your voice, too.

Lis Ermel (they/she/he) is a trauma-informed vocal coach dedicated to helping artists, voice-reliant professionals, and personal growth practitioners develop a voice they can trust.

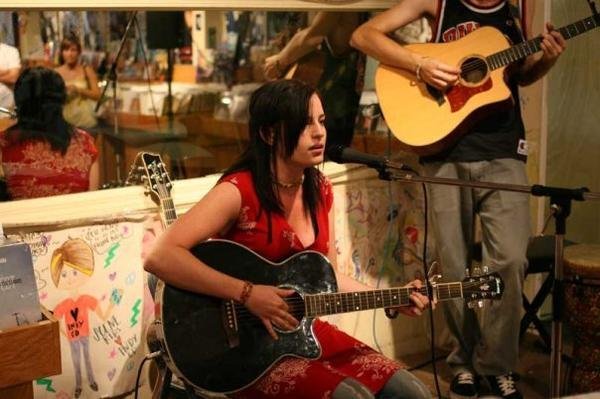

With nearly 25 years in theatre and an MFA in Acting from USC’s School of Dramatic Arts, Lis’ work is deeply rooted in voice, movement, and nervous system regulation. Their professional credits include performances at The Ahmanson Theatre, Mark Taper Forum, and Rockwell Table & Stage, where they co-wrote and starred in the original one-person show "Joan of Arc: Cabaret."

As a queer, neurodivergent, trauma-informed vocal coach and 200hr RYT® yoga teacher, Lis integrates mind, body, and voice to help clients build confidence, release tension, and connect to their fullest expression. Their private practice, Voice with Lis, offers one-on-one coaching and The Virtual Studio membership—an online space for guided training, live coaching, and community support.

When they’re not coaching, performing, or writing, you can find Lis cuddling dogs, overwatering their plants, doomscrolling, and figuring out how to balance rest and ambition.